Encounters with Freud and Frankl in Vienna Part 1: S. Freud

- valvenpsy

- Jan 12, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 13, 2024

One morning, when I had no patients to see, I decided to pay a little visit to Freud, before attending my German class. The privately-owned Sigmund Freud Museum, which was once Freud’s stately three-story house for 47 years, is situated on Bergasse in a bourgeois part of town, close to the Faculty of Medicine, where he once worked in a neurobiology lab. I was welcomed into his cozy waiting room, on the right side of the staircase, across from his family lodgings. Upon the walls hang certificates of Freud’s honorary memberships to the British Psychological Society and the New York Neurological Society, a portrait of Einstein, a reproduction of Fussli’s enigmatic and disturbing “Nightmare” and etchings of the four elements.

Freud dolls... Where else can one find such effigies other than in Vienna?

Freud's waiting room

H. Fussli's "The Nightmare" ("Fussli: Entre rêve et fantastique" exhibit at Musée Jacquemart André, Paris, September 2022)

It was moving to think that this is the place where psychoanalysis, and by extension psychotherapy, were born, as well as the theories that would revolutionize not only Psychology, but permeate most of Western society in some way, and even the course of my own professional life. I imagine that most of my colleagues have at some point been intrigued by Freud’s theories and prolific body of works, as was my case in my teenage years as I discovered psychoanalysis, through literature originally, (through Jean-Paul Sartre’s short story “L’enfance d’un chef” and D.M. Thomas’s “The White Hotel”) and later read some of his works in preparation for an oral presentation of phobias, as the subject to obtain my Alliance Française certificate of proficiency in French. These remote memories all returned as I spent time in the waiting room and then entered Dr. Freud’s consultation room, as his patients, and colleagues (including his illustrious disciples, who developed their own branches of psychoanalysis, C.G. Jung, who developed the concepts of archetypes, the collective unconscious and the spiritual dimension in psychology, and Alfred Adler, well-known for the coining of Superiority-Inferiority Complex and for describing sibling traits according to birth order) attending the weekly exchanges on the developing field of psychoanalysis once did… about a century ago.

The treatment room, which has much changed since the time of Freud, and notably devoid of the seminal couch/ divan (now in London, where Freud and his family were forced to seek exile in 1938, with the rise of National Socialism in Austria) can only be imagined with the aid of a few pictures from the era as a cozy, predominantly crimson room, with an Oriental feel, “inhabited” by antique figurines of “old and dirty gods” of Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Greek, Roman, Etruscan, Chinese and South American origins. Entering such a room sets the tone for Archeology and Exploration of the Mind and Soul… Today, although some of the “old and dirty gods” remain on display, one encounters a collection of Freud’s works and letters from his prolific exchanges with contemporary intellectuals, scientists and artists alike, on topics ranging from the development of his world-changing theories to conjectures of promoting pacifism: “whatever makes for cultural development is working against war”, in his exchange with Albert Einstein on “delivering mankind from the menace of war”. His most renowned concepts and theories are presented to the visitors: Narcissism, the Oedipus complex, the Id/ Ego/ Supergo model of the human psyche, and the ubiquitous Subconscious, which practically became household terms in the 20th century, greatly influencing Western culture and thought.

Freud's collection of ancient gods, goddesses and other mythological figures

In the following rooms, one encounters diverse aspects of Freud’s professional life: his training and work as a neurologist (at the Vienna Children’s Hospital, notably), his research (both clinical, hemiplegia in children, and basic at a neuroanatomy lab), as well as an internship at the Pitié-Sapêtrière Hospital in Paris, where he studied hysteria and hypnosis under Jean-Marie Charcot, an experience that set the stage for the change of course that his life was about to take by the development of psychonanalysis. Freud’s passion for travelling and art, his family[1] and professional legacy in the form of his written works (“The Interpretation of Dreams”) and in his disciples, from Melanie Klein to Jacques Lacan to contemporary analysts, spanning all continents and the last century, provide additional elements in the discovery of the character. Finally, Anna Freud, his beloved youngest daughter, who followed in his professional footsteps, but specializing in child psychology, is also present in the home, just as she was by her father throughout much of his life.

During this visit to the Freud home/ museum, I discovered the open-minded, highly cultivated, well-travelled, polyglot and curious man, very different from the “sexually-obsessed” shrink that Freud-bashing psychologists from other branches of therapy often make him out to be. However, there were some other surprises regarding the complexity of the character that I was yet to discover on the unique Sigmund Freud Tour that I took a few days later…

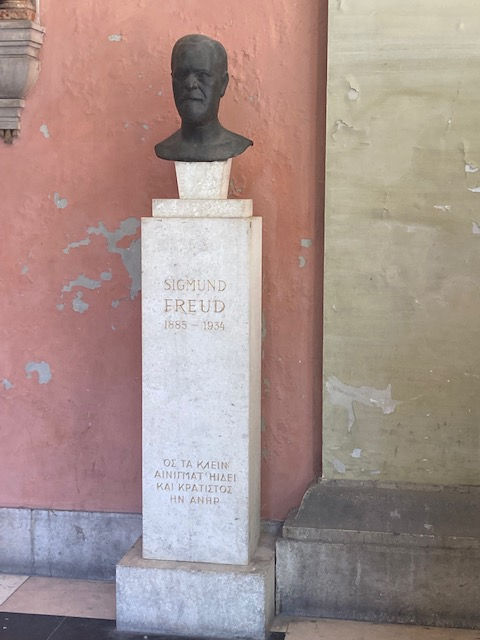

The tour started at the University of Vienna where Freud studied medicine and later conducted basic research in a neuroanatomy lab. Here we became acquainted with a young Freud, still seemingly unsure of himself and of his course in life. A small, insignificant bust of the founder of psychoanalysis (with an erroneous date of birth!) now stands at the end of a row of busts of prominent Austrian scientists, including that of Christian Doppler, a renowned physicist, having made contributions to medical imaging techniques. The next stop was to the official city of Vienna monument to Freud at a nearby park, an unimpressive, engraved gray stone, dramatically contrasting with the beautiful monuments to musicians like W.A. Mozart or J. Strauss in parks in another parts of town. Both of these monuments when taken together seem to indicate the profound misunderstanding, or even disdain, for Freud’s revolutionizing work by the Viennese community of today, just as he apparently was not very accepted in his own day. As the saying goes, “No one is a prophet in their own land.” So, Freud faced rejection from his contemporaries, as he did from some of his peers, and I have no doubt that these difficulties forged his character and independent spirit and mind, preparing him to face greater traumatic events, such as exile and illness in the last years of his life. I also discovered throughout the tour, visiting the hospital campus where he initiated his career, that he battled with depression much of his life, and yet maintained a firm belief in his calling to accomplishment (likely originating in his mother’s unwavering belief in her son’s exceptional abilities). He was eager to share his knowledge and ideas with others who were willing to listen and follow, but intolerant toward dissent (as evidenced by his ruptures with Jung, Adler and many other disciples who dared to disagree with him). Contradictory, paradoxical stances and attitudes marked the founder of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy throughout his life, as these likely mark us all is some manner. He was, and is still praised (and almost venerated[2]) by his disciples of the time and the present-day Freudian analysts, and yet was and is misunderstood and despised by his Viennese contemporaries and by some therapists of other orientations.

University of Vienna,where Freud studied medicine and worked in a neuroanatomy lab

An unflattering bust of Freud at the University of Vienna

Café Central, one of Freud's favourite cafés

Neogothic Café Central

After this encounter with Sigmund Freud in the city where he grew up, started his professional life, established his practice and developed the influential theories of psychoanalysis, I have gotten know the mythical character better, as a complex, tormented, cultivated and creative individual that he was. But rest assured, that this experience has not instilled the desire to “convert” to psychoanalysis, which I find to be interesting from an historical perspective and recognize its contributions to the development of psychotherapy, yet I remain critical of many of its postulates (which remain unproven in scientific terms), and its efficacy in treating mental health issues.

In the next section I will introduce my encounter with the founder of Existential Psychotherapy, Viktor Frankl, whose theories and practices resonate more with my own style of therapy and seem more relevant to one of today’s major challenges in a quickly evolving world: the search for Purpose and Meaning. Stay tuned!

Dr. Val at the Sigmund Freud Museum, Vienna

[1] S. Freud was married to Martha Bernays, whose American-born nephew, Edward Bernays, was instrumental in developing Propaganda techniques, that have been used to manipulate humanity, both commercially and politically, throughout decades. [2] Upon occasion, I have the impression that psychoanalysis is a religion of sorts: dogmatic with a cult-like veneration of Freud.

Amazing discoveries Dr. Valerie! Very impressive, especially the combination of your work as a clinical psycho-analyst, your linguistic background, your love for art and art history, the historical background of these renowned figures and what is still there to be seen and experienced today in Vienna from remains. What completely baffledme was the"Old and Dirty Gods" Froid collection! Thank you very much for this article. I've enjoyed every part of it and left me craving more. 🙃 Wishing you all the best, and many greetings from Madrid,, Tahany Al-Alim.